By Charlotte Silver | Vice | April 1, 2015

In June 1998, an Orange County, California, bank was robbed. Three men made off with a little over a thousand dollars in cash.

At the time, Guy Miles, a 31-year-old black man from nearby Carson, was in violation of parole. Released from a California prison the year before—after spending two years there for stealing cars from a valet service—he was not permitted to leave the state. Miles wanted to break away from the life of gangs, crime, and prison that he had been locked into since dropping out of high school, according to his family.

So he left for Las Vegas, moved in with his new girlfriend, and kept himself afloat by shuttling between small jobs. Miles concealed his whereabouts from his parole officer by telling him he was staying with his parents in Carson, and every so often he would make a dash through the desert to show up for meetings.

In September 1998, Miles’s parole officer asked him to come in for an impromptu meeting. Waiting for him at the office was a police officer with a warrant for his arrest. Two witnesses who’d been working at the Orange County bank at the time of the robbery had fingered Miles. At trial, his Vegas alibi didn’t hold up against prosecutors’ eyewitness testimonies and Miles and another man, Bernard Teamer, were found guilty. (Teamer had allegedly manned the getaway car.)

“During the trial, it was a farce. They were more interested in talking about gang activity than the actual crime,” Miles’s father, Charles, told VICE. He recalled that during the trial, the prosecutor asked Miles to show the courtroom his tattoo to indicate his affiliation with the East Coast 190 Crips.

At the outset, Patlan admitted to the investigators he would not be able to identify the stocky suspect.

With two strikes already on his record, Miles was sentenced to 75 years to life, in accordance with the state’s three strikes law. He has spent the last 17 years locked up at California Men’s Colony in San Luis Obispo.

Criminal justice reform advocates say what happened to Miles shows what’s wrong with the way eyewitness testimony is treated in America. Despite a nationwide trend toward various reforms in law enforcement, during trials a single eyewitness (who may be compromised in one way or another) can outweigh an overwhelming amount of other evidence.

“Off the bat, 35 percent of eyewitness testimonies are wrong,” Rebecca Brown, director of state policy reform at the Innocence Project, told VICE.

While prosecutorial misconduct, including deliberately mishandling witnesses, is present in up to 42 percent of exoneration cases, Brown believes misidentifications are a function of poor protocol.

“What we’ve seen is that the vast majority of mistaken identities is not the intention of police, but just them doing the normal procedures of the time,” she said.

Decades of sociological and psychological research suggest the way police departments have traditionally conducted photo lineups is akin to trampling through a crime scene with muddy boots on.

“Everyone agrees that it’s what happens at the front end of the criminal justice system that leads to wrongful convictions,” John Furman, the director of research at the International Association of Police Chiefs (IAPC), said in an interview.

Experts and advocates recommend that police conduct double-blind sequential photo lineups in order to ensure the process is as pristine as possible. This means that instead of showing six mugshots at once (“six-packs”), a witness is shown one photo at a time, and the police officer conducting the lineup doesn’t know who the suspect is. Finally, the sessions should be recorded and the witness admonished that the perpetrator may or may not be in the lineup.

“Witness identification is legally supposed to be independent, so if the detective contributes to the witnesses’ decisions in some way, then it’s not independent,” according to Jennifer Dysart, an associate professor of psychology at John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

Dysart is one of many psychologists who believe that without blind administration, the reliability of the eyewitness process is jeopardized. She has studied the dynamic between a witness and a detective during photo lineups, and has observed that when an officer knows the identity of the suspect in the lineup, all kinds of subtle cues pass from the detective to the witness. A barely visible shift of the body. A nod of the head. A smile. Even the act of showing witnesses additional photos after they’ve indicated that one photo resembles the perpetrator can signal they haven’t chosen “correctly.”

As surely as physical evidence collected at a crime scene can be contaminated purposely or through carelessness, a witness’s memory can be sullied and rendered invalid. In Miles’s case, police began the process of contaminating the witnesses’ already shaky memories as soon as they created the six-packs, according to advocates and experts who reviewed the case.

The two bank employees, Trina Gomez and Max Patlan, did not have a clear recollection of the two men who held them up, according to court documents. They knew that both men were black; one of the men was short and stocky and the other slender and maybe taller. The “stocky” man was said to have a shaved head, facial hair and “rolls on the back of his neck.”

At the outset, Patlan admitted to the investigators he would not be able to identify the stocky suspect. The man had struck him on the face with the butt of a gun, pushed him to the ground, and shouted to him and Gomez to “do as they were told.”

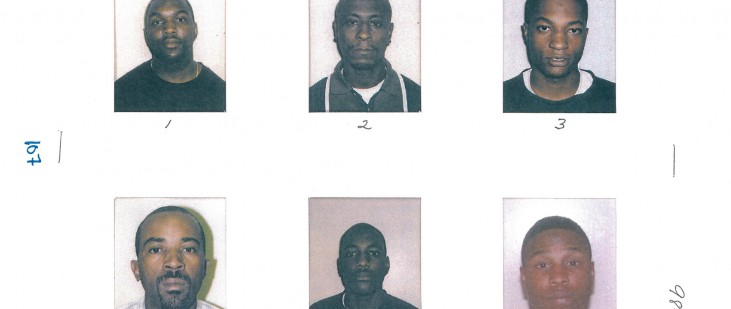

Nevertheless, Detective Michael Montgomery, the lead investigator, presented the witnesses with a total of 48 mugshots. He told the three witnesses that the police had arrested two suspects. During the process, the witnesses picked several photos of different people, suggesting they resembled the men who robbed the bank.

After a quick meeting with the prosecutors, during which she was directed to look at Miles’ mugshot again, Gomez returned to the witness stand and stated for the jury, without hesitation, that Miles was the man.

Miles’s mugshot appeared in the last set. His picture shows him with close-shaven hair, a shadow of a beard, and drooping shoulders. Miles was selected by Gomez and Patlan as the “stocky” man who had waved a gun around that June night, the man Patlan had suggested he would not be able to identify.

But when Trina Gomez took the stand at the trial a few months later, she stared at Miles sitting at the table next to his lawyer and said, not in the presence of the jury, “He looks different.” Pausing, and then viewing him from another angle: “I’m sure that that’s him in the photo, but I’m not sure if that’s him over there.”

After a quick meeting with the prosecutors, during which she was directed to look at Miles’s mugshot again, Gomez returned to the witness stand and stated for the jury, without hesitation, that Miles was the man.

That faulty eyewitness identifications are a prodigious source of false convictions has become an almost undisputed realm for police reform. Research recommending new methods of showing photo lineups to witnesses is as old as the 1970s, but changes didn’t begin to be implemented until the 2000s.

In 2013, IAPC recommended police departments adopt the double-blind sequential photo lineup method, and last year the National Academy of Science endorsed the blind administration of witness lineups,while remaining neutral on the issue of sequential versus simultaneous photos lineups.

Jurisdictions with reformed practices report the transition was pretty simple, requiring no extra man hours or costs and just a few simple adjustments to the routine lineup.

Santa Clara County, in Northern California, switched to the double-blind sequential method in 2003. David Angel, who works in the county’s Convictions Integrity Unit, told VICE that since his jurisdiction adopted new methodology for photo lineups, they have have had no known cases of a wrongful conviction due to a misidentification.

“You begin to look at witness identification as trace evidence,” Angel said. “You don’t want to contaminate the evidence.”

“There’s growing public awareness and there’s also a great deal of law enforcement leadership in this area,” Brown, of the Innocence Project, said. Her organization has documented a handful of states that have implemented the package of reforms.

But Southern California, including Los Angeles and Orange County—the jurisdiction that convicted Miles—remains a significant holdout.

Though IAPC has recommended departments adopt the double-blind sequential method, many resist the change. “If a department hasn’t had convictions overturned, they aren’t going to think they need to modify their method,” Furman told me.

“We feel like it is time for a city like Los Angeles to lead in this area, and we are hopeful that through a series of conversations that they will be hopeful,” Brown added.

About a quarter of the cases the Innocence Project is working on in Southern California right now involve a faulty eyewitness, and yet jurisdictions there have yet to adopt the few simple reforms that have been implemented in the northern part of state and around the country.

Asked why Orange County has not changed its photo lineup methods, Lieutenant Ken Burmood of the Orange County Sheriff’s Department told VICE, “That’s the way we do it, and we’ve done it that way for a long time.”

He added, “We haven’t run into any of those problems where an officer or a detective has led anyone in a different direction.”

Miles might beg to differ.

After his conviction and imprisonment, Miles tried to find the real perpetrators of the crime. His parents, both ministers in Carson, helped him. They sold their house in Atlanta and invested all their money and time trying to do what they believed the police had failed to. The couple hired a private investigator and used their immediate network of neighbors and friends to try to piece together a trail to the real culprits.

In 2002, the California Innocence Project picked Miles’s case out of the thousands of pleas for assistance they receive each year. By 2007, two men, Harold Bailey and Jason Steward, had been tracked down. Bailey had been one of the 48 men whose photos had been shown to the witnesses in 1997, and one of the several that Gomez said looked “familiar.” Both men eventually signed confessions that included minute details of the 1997 burglary.

In 2013, in response to Miles’s petition, a California Appeals Court awarded Miles an evidentiary hearing. In preparation for the hearing, the Miles family lined up their witnesses again, including the two men who had confessed. By now both were in prison for unrelated crimes. The district attorney’s office fought to uphold Miles’s conviction, as a matter of routine and because Trina Gomez and Max Patlan had not recanted their original testimonies.

At the evidentiary hearing, Teamer, who had originally pleaded not guilty, admitted that he had helped organize the robbery and that Miles had never been involved. Teamer testified that he hadn’t told the truth at the original trial time because he was too afraid of retribution to snitch on fellow gang members.

Miles’s defense team presented the confessions, Miles’s alibi, and the updated scientific research on the fallibility of the photo lineup methodology the police had used to collect their testimonies.

But the assigned referee, Judge Thomas Goethals, ruled the confessions of these convicted felons “uncredible” and recommended the Appellate Court uphold Miles’s conviction, even while acknowledging that he “could in fact be innocent.” The fact that the eyewitnesses were sticking to their original testimonies essentially meant that Goethals could not rule that the prosecution’s case had been undermined.

Miles, who completed his high school degree in prison, is now waiting for the Appeals court to make the final ruling on whether he should receive a new trial. (VICE reached out to the DA’s office to ask about Guy Miles and their position on eyewitness identification reform, and they did not respond for comment.)

“We presented evidence that the system variables directly led to a misidentification, we had three people saying they committed the crime–not Guy,” Alex Simpson of the California Innocence Project at the California Western School of Law told VICE. “But even in that situation, we couldn’t reverse it. It shows you how powerful eyewitness testimony is.”

Read the original post on Vice.