By Michael N. Tennison, MA

In the early 1990s, visionary futurist Terence McKenna hypothesized that two seemingly disparate modalities of consciousness alteration and extension—drugs and computers—might ultimately converge. If he were still alive today, even Terence might be surprised at the accuracy of his assessment.

As reported by the Boston Globe on February 8, Thync, a company marketing a new neuro-enhancement device to be released later this year, purports to give users computerized control over fundamental elements of consciousness, including mood, cognitive capacities, and energy levels. Enticing the potential consumer to “shift [one’s] state of mind” and “conquer life,” Thync claims its device can stimulate neural pathways with “intelligent waveforms,” or “vibes.” Different “vibes,” they claim, produce results akin to a coffee-induced jolt on one hand or an alcohol-induced relaxation on the other. The Thync prototype appears to rely on transcranial direct-current stimulation (tDCS), a mechanism that sends very low-level currents of electricity through the brain. Scientists hypothesize that these low levels of electricity may produce subthreshold stimulation. This means that the current gives neurons just enough of a boost to prime them to fire – without exciting them enough to cause firing. Researchers believe that this may put neurons in a state of readiness to engage in neuroplasticity, enabling neurological changes that may be useful for patients and healthy consumers alike.

Reporters have been awed by the potential of consumer-grade brain stimulation to enhance all sorts of neurologically-mediated capacities, from learning and focus to attention and mood. In 2012, one reporter stated that a 20 minute session of tDCS induced a Zen-like state of deep calm that facilitated the near-instant acquisition of new skill sets, lasting for several days until finally tapering off completely. Recent studies, on the other hand, suggest that single-session tDCS interventions may deliver little more than the placebo effect. In a review of 59 analyses, Australian researchers found tDCS to have no significant effect on executive function, memory, language, or other cognitive capacities. Despite the data’s inconclusiveness—not to mention lack of FDA approval for therapeutic use—tDCS can be purchased online and even built in an afternoon with parts from a standard electronics store.

Online forums dedicated to personal tDCS use have sprung up across the internet, typically encouraging the use of studied protocols with respect to electrode placement, duration of application, and level of current. Many intrepid users freely experiment, seeking to probe the edges of consciousness not unlike psychedelic explorers of yesteryear. This, of course, raises the chief concern about tDCS: regardless of whether or not the device can bring about the desired mental states, users place themselves at risk of harm either by mistake or misadventure.

When administered by trained scientists in a research setting, tDCS appears to have few, if any, negative effects. The most serious reported negative effects pertain to skin irritation caused by electrodes. Little to no evidence is available, however, about long-term risks. One can certainly imagine a situation in which tDCS does bring about the desired results, to which users habituate or addict, either requiring ever-greater doses of electricity or otherwise interfering with their lives. In addition, the risks of novel parameter configurations employed by home users, such as placement of the electrodes—selected either intentionally or by mistake—may not have been studied, and new risks could emerge.

Companies like Thync and others could mitigate some of these risks. By programming parameter limitations into its device’s operating software, foc.us limits the duration and intensity of the electricity it produces. Yet, just as tinkerers have been able to “jailbreak” their smartphones, such a practice may be possible with tDCS devices.

How much protection should consumers have at this point from commercial tDCS devices and their own experimentation? In a counterintuitive twist, tDCS must be approved by FDA if it is marketed “therapeutically” – that is, to treat or cure any medical condition. Yet, when marketed for private, non-therapeutic use the same device escapes FDA’s regulatory authority. Whether the device is used therapeutically or recreationally could boil down to different semantic characterizations of exactly the same thing. And is enhancement – helping junior learn his multiplication tables faster, for example – “therapeutic” or “recreational”? So far, the FDA has not explicitly weighed in, but it recently released a draft guidance exempting “low risk general wellness products” from regulation as medical devices; whether this applies to tDCS, however, is unclear.

Should this apparent regulatory loophole be of concern? After all, as a society we not only permit but encourage all sorts of activities that carry substantial risks for the participants, such as sky diving, motorcycle riding, and football. This deference to rugged individualism and autonomy is deeply embedded in American culture. But when it comes to risks associated specifically with alterations of consciousness, the government tends to be more paternalistic, if not consistent, in its approach to individual liberty. Recreational drug use is prohibited unless it involves only our society’s politically-sanctioned drugs of choice—caffeine, tobacco, and alcohol.

This bifurcation has little to do with safety: tobacco contributes to more deaths per year than all illegal drugs combined. What is, or is not, permitted is a fundamentally political choice. Thus, the emergence of commercial tDCS can and should prompt a new discussion about the regulation of consciousness alteration, whether performed by chemical or technological means.

Michael Tennison is a JD candidate (’15) at the University of Maryland.

James Giordano, PhD is Chief of the Neuroethics Studies Program at the Pellegrino Center for Clinical Bioethics and is Co-direector of the O’Neill-Pellegrino Program in Brain Science and Global Health Law and policy. He is also a professor in the Department of Neurology at Georgetown University Medical Center in Washington, DC.

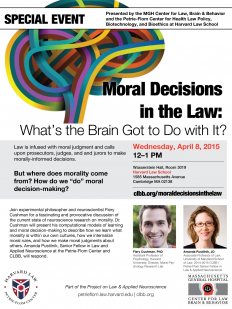

James Giordano, PhD is Chief of the Neuroethics Studies Program at the Pellegrino Center for Clinical Bioethics and is Co-direector of the O’Neill-Pellegrino Program in Brain Science and Global Health Law and policy. He is also a professor in the Department of Neurology at Georgetown University Medical Center in Washington, DC. Ekaterina (Kate) Pivovarova, PhD is a Researcher and Assistant Professor in the Law and Psychiatry Division at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, Department of Psychiatry. She is also a licensed Clinical Psychologist in private practice. Dr. Pivovarova was the 2013-2014 CLBB Forensic Psychology Research Fellow.

Ekaterina (Kate) Pivovarova, PhD is a Researcher and Assistant Professor in the Law and Psychiatry Division at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, Department of Psychiatry. She is also a licensed Clinical Psychologist in private practice. Dr. Pivovarova was the 2013-2014 CLBB Forensic Psychology Research Fellow. Francis X. Shen, PhD, JD is a McKnight Landgrant Professor and Associate Professor of Law at the University of Minnesota, where he directs the Shen Neurolaw Lab. He also serves as Executive Director of Education and Outreach for the MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Law and Neuroscience, and is currently a visiting scholar at the Petrie-Flom Center for Health Law Policy, Biotechnology, and Bioethics at Harvard Law School.

Francis X. Shen, PhD, JD is a McKnight Landgrant Professor and Associate Professor of Law at the University of Minnesota, where he directs the Shen Neurolaw Lab. He also serves as Executive Director of Education and Outreach for the MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Law and Neuroscience, and is currently a visiting scholar at the Petrie-Flom Center for Health Law Policy, Biotechnology, and Bioethics at Harvard Law School.