By Kamala Kelker | The Guardian | January 17, 2016

It’s hard to imagine Steven Northington killing two people. The 43-year-old says he likes to make people laugh, “like a comedian”. He’s a loyal son to his troubled mother and father. He sends his younger sister birthday cards from prison and draws elaborate smiley faces on them. His defense team laughs with affection when they hear his name because he is, they say, “a character”.

Between 2003 and 2004, Northington was slinging for a drug ring that flooded his Philadelphia neighborhood with bloodshed. The Kaboni Savage Organization was responsible for nine murders during those two years alone, including the firebombing of a house that killed two women and four children.

The government was after them, and they knew it: seven of the nine victims were murdered in retaliation against witnesses who had agreed to cooperate with prosecutors to bring the kingpin down, according to the FBI.

It wasn’t until 2013 that the federal court started its trial against ringleader Kaboni Savage, as well as his sister Kidada Savage, accomplice Robert Merritt, and Northington. The four were tried together for a total of 12 murders dating back to 1998.

Northington stood apart because he was arrested a month before the firebombing, and only charged for two of the murders – those of Barry Parker, a corner competitor of the ring, and Tybius Flowers, a childhood friend. In Flowers’s case, the execution happened hours before he was supposed to take the stand as the star witness against Savage in a 1998 murder case.

Northington was convicted by the state court in Philadelphia in 2007 for the murder of Parker. In 2013, the federal trial combined the two murders and found Northington guilty of aiding both.

And since the murders were an attempt to intimidate witnesses and in support of racketeering, federal prosecutors wanted him dead.

They asked for the death penalty.

•••

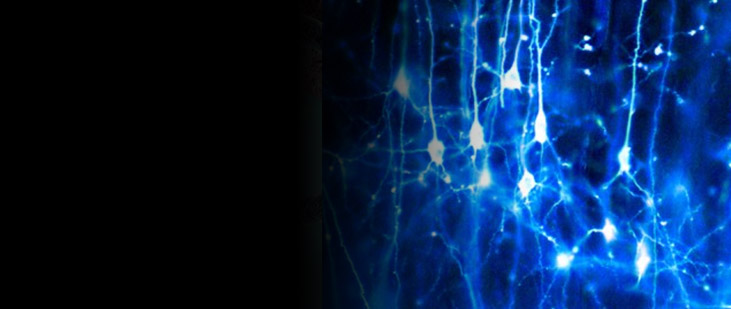

Days before he was sentenced, one of Northington’s lawyers, William Bowe, showed the jurors something they never saw during the six-month trial: images of Northington’s brain. He told them that Northington was developmentally stunted by homelessness, abuse and prenatal exposure to drugs and alcohol.

Bowe said the deficiencies the scans revealed provided some explanation for Northington’s actions – not an excuse, but an extenuating set of circumstances.

“What does that mean? It means that Steven Northington doesn’t think like you and me. It means his brain doesn’t function like ours. It means when he makes a decision, he doesn’t do it like you or me. It’s broken,” he told the jury.

Brain images are becoming standard evidence in some of the country’s most controversial and disturbing death penalty cases. In March, Barack Obama’s bioethics commission released a report stating that neuroscience is used in about a quarter of capital cases, and that percentage is rising quickly.

Lawyers use scans in a few principal ways. Sometimes it’s to explain a psychiatrist’s diagnosis to help a plea of insanity, or to help prove intellectual disability. Most often they are used to ask juries for mercy during the sentencing phase of the grimmest trials.

Since the inner workings of a criminal’s mind are central to a case, any tool that might shed light on the 3-lb organ is worth considering. And brain scans have diagnostic credibility: they are fundamental in clinical settings for spotting tumors, cancer or traumatic injuries. They have been used to study aspects of behavior, such as decision-making, depression and impulse control. But in death penalty cases, the images are taken out of that medical or experimental context, and used to clarify nuances of criminal actions.

It remains unclear whether pictures of neural processes or of brain anatomy can reveal a person’s morals or the substance of their character. But despite incomplete science, brain scans are becoming crucial arbiters of life and death.

Continue reading the full article here.

This article was originally published by The Guardian.