CLBB Scientific Faculty Member Dr. Charles Nelson was featured in this article for his role in an unprecedented study in Bangladesh connecting poverty and child development. The study, which originated in the slums of Dhaka and is led by Shahria Hafiz Kakon, employs brain imaging to study children with stunted growth. About the study, and Dr. Nelson’s role, the article notes:

About five years ago, the Gates Foundation became interested in tracking brain development in young children living with adversity, especially stunted growth and poor nutrition. The foundation had been studying children’s responses to vaccines at Kakon’s clinic. The high rate of stunting, along with the team’s strong bonds with participants, clinched the deal.

To get the study off the ground, the foundation connected the Dhaka team with Charles Nelson, a paediatric neuroscientist at Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Massachusetts. He had expertise in brain imaging—and in childhood adversity. In 2000, he began a study tracking the brain development of children who had grown up in harsh Romanian orphanages. Although fed and sheltered, the children had almost no stimulation, social contact or emotional support. Many have experienced long-term cognitive problems.

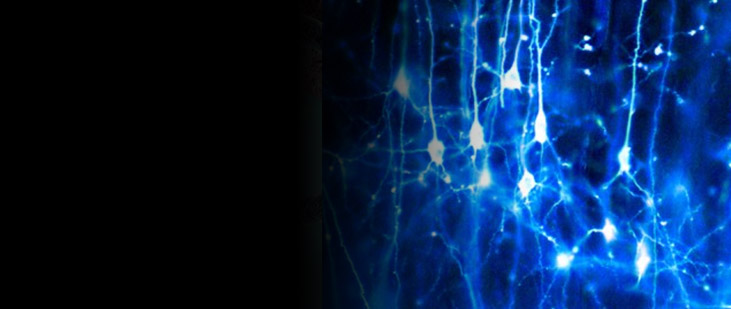

Nelson’s work revealed that the orphans’ brains bear marks of neglect. MRIs showed that by the age of eight, they had smaller regions of grey and white matter associated with attention and language than did children raised by their biological families. Some children who had moved from the orphanages into foster homes as toddlers were spared some of the deficits.

The children in the Dhaka study have a completely different upbringing. They are surrounded by sights, sounds and extended families who often all live together in tight quarters. It is the “opposite of kids lying in a crib, staring at a white ceiling all day”, says Nelson.

But the Bangladeshi children do deal with inadequate nutrition and sanitation. And researchers hadn’t explored the impacts of such conditions on cerebral development. There are brain-imaging studies of children growing up in poverty—which, like stunting, could be a proxy for inadequate nutrition. But these have mostly focused on high-income areas, such as the United States, Europe and Australia. No matter how poor the children there are, most have some nutritious foods, clean water and plumbing, says Nelson. Those in the Dhaka slums live and play around open canals of sewage. “There are many more kids like the kids in Dhaka around the world,” he says. “And we knew nothing about them from a brain level.”

To read more about the study and its findings, read the rest of the article, “How Poverty Affects the Brain”, published by Scientific American on July 12, 2017.