By Frank Porreca and Theodore Price | Scientific American Mind | September 2009

Imagine you are a doctor treating a patient who has been in nearly constant pain for four years, ever since the day he sprained his ankle stepping off a curb. Physical therapy only briefly dulled the agony. Painkillers were not much better, and the most effective drugs made your patient exhausted and constipated. He is now depressed, sleeping poorly and having difficulty concentrating. As you talk with him, you realize that his thinking also seems impaired. Your exam confirms that the original injury has healed. Only pain and its consequences remain—and your options for helping this man are running out.

This scenario plays out every day in doctors’ offices around the world. Fifteen to 20 percent of adults worldwide suffer from persistent, or chronic, pain. Half the primary care patients who develop a chronic pain condition fail to recover within a year, according to surveys conducted by the World Health Organization. Common causes of such unrelenting discomfort include physical trauma, arthritis, cancer, and metabolic diseases such as diabetes that can damage nerves. In many cases, however, the pain’s origins are mysterious.

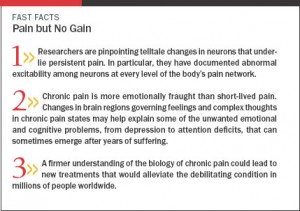

Indeed, despite decades of intense research into the biology of pain and how pain is perceived, many mysteries still surround chronic pain and its treatment. No one knows for sure why some injuries, even minor ones, result in persistent pain or why it occurs in some people but not in others. Nevertheless, researchers are pinpointing telltale changes in the neurons that underlie persistent pain. In particular, they have documented abnormal excitability among neurons at every level of the body’s pain network. For instance, in the spinal cord, some cells aberrantly amplify pain signals after undergoing a type of molecular “learning” that is similar to what happens in the brain during the formation of long-term memories.

Indeed, despite decades of intense research into the biology of pain and how pain is perceived, many mysteries still surround chronic pain and its treatment. No one knows for sure why some injuries, even minor ones, result in persistent pain or why it occurs in some people but not in others. Nevertheless, researchers are pinpointing telltale changes in the neurons that underlie persistent pain. In particular, they have documented abnormal excitability among neurons at every level of the body’s pain network. For instance, in the spinal cord, some cells aberrantly amplify pain signals after undergoing a type of molecular “learning” that is similar to what happens in the brain during the formation of long-term memories.

Chronic pain is more emotionally fraught than acute pain—which comes on quickly but lasts a relatively short time. Changes in brain regions governing feelings and complex thoughts in chronic pain states may help explain some of the unwanted emotional and cognitive problems, from depression to attention deficits, that can sometimes emerge after years of suffering. Researchers have even uncovered signs that chronic pain might be a type of neurodegenerative disease, affecting parts of the brain that deal with attention, memory and decision making. A firmer understanding of these processes could lead to new treatments that would alleviate the relentless chronic pain experienced by millions of people worldwide.