Part of the ongoing coverage of Dr. Lisa Feldman Barrett’s new book, How Emotions Are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain.

By Lisa Feldman Barrett | The New York Times | March 11, 2017

In the 1992 Supreme Court case Riggins v. Nevada, Justice Anthony M. Kennedy acknowledged — perhaps unwittingly — that our legal system relies on a particular theory of the emotions. The court had ruled that a criminal defendant could not forcibly be medicated to stand trial, and Justice Kennedy concurred, stressing that medication might impair a defendant’s ability to exhibit his feelings. This, he warned, would interfere with the critical task, during the sentencing phase, of trying to “know the heart and mind of the offender,” including “his contrition or its absence.”

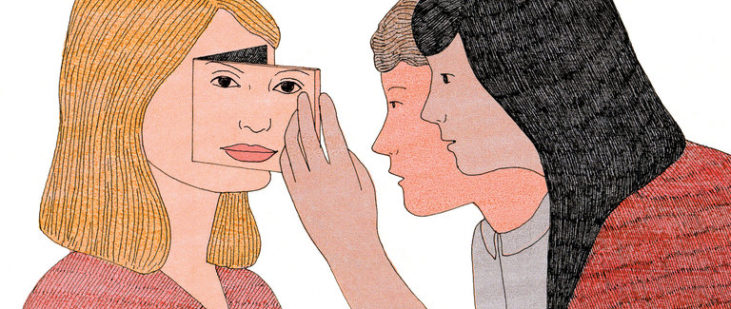

But can a judge or jurors infer a defendant’s emotions reliably, as Justice Kennedy implied? Is it possible, as this theory holds, to detect remorse — or any other emotion — just by looking and listening?

Some scientists believe so. A famous experimental paradigm called “mind in the eyes” purports to demonstrate this ability. You are shown a photograph of a pair of eyes, accompanied by a short list of words that describe a mental state or attitude, such as irritated, sarcastic, worried and friendly. Then you are asked to pick the word that best matches the emotions the eyes express. My lab has confirmed that test subjects perform marvelously at this task, selecting the expected word more than 70 percent of the time on average, based on a study we conducted using over 100 test subjects.

My lab, however, has also discovered a hitch in this paradigm: If you remove the list of words and ask test subjects to “read” the eyes alone, their performance plummets to about 7 percent on average. The word list, it seems, acts as a cheat sheet that helps test subjects unconsciously narrow down the possibilities. People turn out to be quite bad at inferring emotions without context. This includes judges and juries.

Our legal system is one of the most impressive feats of Western civilization. But psychology and neuroscience in recent years have shown many of its tacit assumptions to be out of sync with our best understanding of how our brains and minds work.

Consider another important part of our legal system: witnesses. They testify about what they saw and heard. If you were on the witness stand and had honest intentions, you might think you could carry out this job accurately. However, sights and sounds do not simply flow into your eyes and ears to be stored by your brain. Visual and auditory input from the world play only a part in what you see and hear.

A clever study published in the Stanford Law Review in 2012 illustrated this point. Experimenters played a video of protesters being dispersed by police and asked viewers whether the protesters were peaceful or violent. Even though everyone watched the identical action onscreen, viewers’ perceptions varied with their political beliefs. When the experimenters described the protesters as anti-abortion activists, viewers with liberal leanings saw the protesters’ actions as violent, whereas the more conservative subjects saw them as peaceful.

Conversely, when the experimenters said the protesters were gay rights proponents, the liberals saw a peaceful protest and the conservatives saw a violent one. Every perception, no matter how objective it seems to the witness, is infused with personal beliefs.

It’s not even clear that judges are reliable arbiters of what they are feeling. In a 2011 study, scientists in Israel found that judges were significantly more likely to deny parole to a prisoner if the hearing was just before lunchtime. The judges evidently experienced their bodily feelings not as hunger but as attitudes about the prisoners in front of them. Immediately after lunch, the judges began granting paroles with their customary frequency.

The idea of inferring mental states is so intuitive that we assume, as Justice Kennedy did, that it’s part of a universal human nature. But it’s not. My lab has visited several remote cultures, far from Western civilization, that view emotions as mere actions, rather than something you feel. These cultures, which include the Himba of Namibia and the Hadza hunter-gatherers of Tanzania, see someone who is smiling and laughing as just smiling and laughing — not “happy,” a word that implies a mental state. In these cultures, physical actions, not mental states, are sufficient to help predict a person’s next action, and moral responsibility for harm is less based on intention.

Today’s science of mind and brain has much to offer the legal system. By educating judges, jurors, attorneys, witnesses, police officers and other legal actors about common-sense assumptions that are scientifically unjustified, we could take steps toward a legal system that is fairer. Even the most fundamental practices, such as trial by jury, could stand some debate, given how jurors’ brains are wired.

In the meantime, a few simple measures, like informing legal actors that they are guessing a defendant’s emotional state, not objectively reading emotions in faces, bodies and voices, could improve the current situation and better protect our rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

Lisa Feldman Barrett, PhD is a University Distinguished Professor at Northeastern University, and a member of the CLBB Scientific Faculty.

Read the full article, originally published in The New York Times.