By Nancy Gertner | The Boston Globe | March 6, 2017

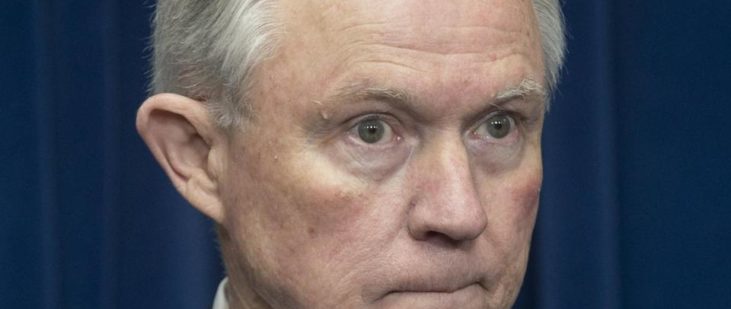

That Attorney General Jeff Sessions made a false statement under oath before a congressional committee is clear. He said, “I did not have communications with the Russians,” when in fact he had met twice with Russian Ambassador Sergey Kislyak. The only question is what the consequences should be.

Making a false statement under oath before Congress is a crime punishable by five years imprisonment when three tests are satisfied: (1) The statement is false, (2) it concerns a material fact, not a minor or incidental one, and (3) the speaker has made the statement willfully and knowingly. The first two are not debatable. Sessions admitted to the meetings with the Russian ambassador. And it was material: Russia’s meddling in the election and whether Trump aides had a role in it has been front and center to Congress.

The only open question is Sessions’ state of mind. A statement that is the product of “confusion, mistake, or faulty memory” does not qualify for criminal prosecution. Some commentators have suggested that there is no basis to go further here: Senator Al Franken’s question was about preelection contacts between Russia and those affiliated with the Trump campaign. When Sessions answered, he didn’t mention the Kislyak meetings, because they concerned his role on the Armed Services Committee. While that may well be true, as The New Yorker’s Jeffrey Toobin suggests, the claim needs to be investigated: What were these meetings about?

But Sessions’ comments are worth investigating even if the encounters with Kislyak were as he described them. A witness may be guilty of a false statement even if he offers false information not called for by the question. That’s why every lawyer advises the client to “just answer the question”; don’t volunteer. In response to a Franken’s question, Sessions volunteered a broad denial: “I did not have communications with the Russians.” There is a law school exam question here: A witness is asked, “Who killed the victim?” and he answers, “I wasn’t present.” The reply may be unresponsive, but if it was untrue, material, and made willfully and knowingly, he should be prosecuted.

Consider the context: a confirmation hearing of a senator who had participated in or presided over such hearings for 20 years. I know about such hearings. When I appeared before the Senate Judiciary Committee as part of my confirmation as a US district court judge in 1992, I was prepared for days by staffers from Senator Kennedy’s office, the Department of Justice, and representatives of the White House counsel. I was asked to go through everything in my record that could conceivably be the subject of the Senate’s questioning. Surely then-Senator Sessions was similarly prepared. Indeed, he knew exactly what was on the minds of his fellow senators; he was one of them.

In fact, Sessions had to know all about prosecutions for lying brought in federal court under circumstances far more murky than this. The law not only makes it a crime to lie to Congress, but also to lie to the FBI, or any federal law enforcement officer. Citizens can be prosecuted even if they don’t know that lying to agents is a felony. Nor are they warned that they can choose not to speak with such officials. (If you are not in custody, there are no Miranda warnings.) The proceedings are not tape-recorded; agents interview individuals in pairs so that one can attest to the statements made, making it difficult to defend.

Take Robel Phillipos, for example. The US Court of Appeals for the First Circuit just upheld Phillipos’s conviction for lying to the FBI about whether he had been in Dzhokhar Tsarnaev’s dormitory room after the Boston Marathon bombing, and about what he saw, even though he was not charged with complicity with the Tsarnaev brothers. His defense was that he was a frightened 19-year-old, high on drugs, and so confused that he wasn’t sure what he had told investigators.

Not so with Senator Sessions. He knew the setting like the back of his hand, the goal of the questioning, the consequences of not telling the truth. He was seeking to be confirmed as the nation’s chief law enforcement officer. Should this be investigated further? Of course.

Judge Nancy Gertner (ret.), is a Senior Lecturer on Law at Harvard University, and the Managing Director of CLBB.

Read the full article, originally published in The Boston Globe.