CLBB Faculty Member Leah Somerville and her work on adolescent development are featured in the following article, which highlights the difficulty in determining a distinct line between adolescence and adulthood. Additional coverage about how her work intersects with the CLBB can be found here.

By Carl Zimmer | The New York Times | December 21, 2016

Leah H. Somerville, a Harvard neuroscientist, sometimes finds herself in front of an audience of judges. They come to hear her speak about how the brain develops.

It’s a subject on which many legal questions depend. How old does someone have to be to be sentenced to death? When should someone get to vote? Can an 18-year-old give informed consent?

Scientists like Dr. Somerville have learned a great deal in recent years. But the complex picture that’s emerging lacks the bright lines that policy makers would like.

“Oftentimes, the very first question I get at the end of a presentation is, ‘O.K., that’s all very nice, but when is the brain finished? When is it done developing?’” Dr. Somerville said. “And I give a very nonsatisfying answer.”

Dr. Somerville laid out the conundrum in detail in a commentary published on Wednesday in the journal Neuron.

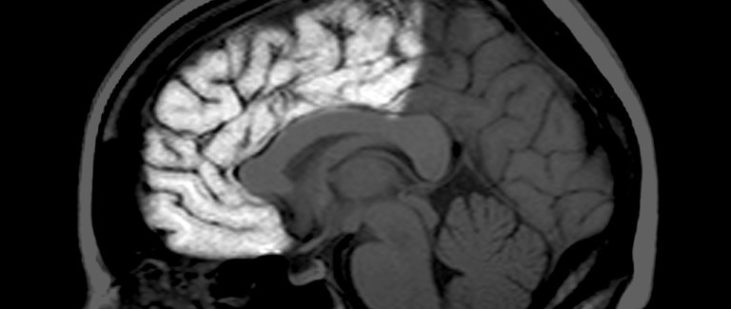

The human brain reaches its adult volume by age 10, but the neurons that make it up continue to change for years after that. The connections between neighboring neurons get pruned back, as new links emerge between more widely separated areas of the brain.

Eventually this reshaping slows, a sign that the brain is maturing. But it happens at different rates in different parts of the brain.

The pruning in the occipital lobe, at the back of the brain, tapers off by age 20. In the frontal lobe, in the front of the brain, new links are still forming at age 30, if not beyond.

“It challenges the notion of what ‘done’ really means,” Dr. Somerville said.

As the anatomy of the brain changes, its activity changes as well. In a child’s brain, neighboring regions tend to work together. By adulthood, distant regions start acting in concert. Neuroscientists have speculated that this long-distance harmony lets the adult brain work more efficiently and process more information.

But the development of these networks is still mysterious, and it’s not yet clear how they influence behavior. Some children, researchers have found, have neural networks that look as if they belong to an adult. But they’re still just children.

Dr. Somerville’s own research focuses on how the changes in the maturing brain affect how people think.

Adolescents do about as well as adults on cognition tests, for instance. But if they’re feeling strong emotions, those scores can plummet. The problem seems to be that teenagers have not yet developed a strong brain system that keeps emotions under control.

That system may take a surprisingly long time to mature, according to a study published this year in Psychological Science.

The authors asked a group of 18- to 21-year-olds to lie in an fMRI scanner and look at a monitor. They were instructed to press a button each time they were shown faces with a certain expression on them — happy in some trials, scared or neutral in others.

And in some cases, the participants knew that they might hear a loud, jarring noise at the end of the trial.

In the trials without the noise, the subjects did just as well as people in their mid-20s. But when they were expecting the noise, they did worse on the test.

Brain scans revealed that the regions of their brains in which emotion is processed were unusually active, while areas dedicated to keeping those emotions under control were weak.

“The young adults looked like teenagers,” said Laurence Steinberg, a psychologist at Temple University and an author of the study.

Dr. Steinberg agreed with Dr. Somerville that the maturing of the brain was proving to be a long, complicated process without obvious milestones. Nevertheless, he thinks recent studies hold some important lessons for policy makers.

He has proposed, for example, that the voting age be lowered to 16. “Sixteen-year-olds are just as good at logical reasoning as older people are,” Dr. Steinberg said.

Courts, too, may need to take into account the powerful influence of emotions, even on people in their early 20s.

“Most crime situations that young people are involved in are emotionally arousing situations — they’re scared, or they’re angry, intoxicated or whatever,” Dr. Steinberg said.

Dr. Somerville, on the other hand, said she was reluctant to offer specific policy suggestions based on her brain research. “I’m still in the learning stage, so I’d hesitate to call out any particular thing,” she said.

But she does think it is important for the scientists to get a fuller picture of how the brain matures. Researchers need to do large-scale studies to track its development from year to year, she said, well into the 20s or beyond.

It’s not enough to compare people using simple categories, such as labeling people below age 18 as children and those older as adults. “Nothing magical occurs at that age,” Dr. Somerville said.

Leah Somerville, PhD is an Associate Professor of Psychology at Harvard University and a member of the CLBB Scientific Faculty.