By Wesley Lowery, Kimberly Kindy, and Keith L. Alexander | The Washington Post | June 30, 2015

It was not yet 9 a.m., and Gary Page was drunk. The disabled handyman had a long history of schizophrenia and depression and, since his wife died in February, he had been struggling to hold his life together.

That bright Saturday morning in March, something snapped. Page, 60, slit his wrists, grabbed a gun and climbed the stairs to his stepdaughter’s place in the Pines Apartments in Harmony, Ind. He said he wanted to die. And then he called 911.

“I want to shoot the cops,” Page slurred to the dispatcher, prodding his stepdaughter to confirm that, yes, he had a gun. “I want them to shoot me.”

Minutes later, Page’s death wish was granted. Two Clay County sheriff’s deputies arrived to find that he had taken a neighbor hostage. They opened fire, striking him five times in the torso and once in the head. Page’s gun later turned out to be a starter pistol, loaded only with blanks. His threats of violence turned out to be equally empty, the product of emotional instability and agonizing despair.

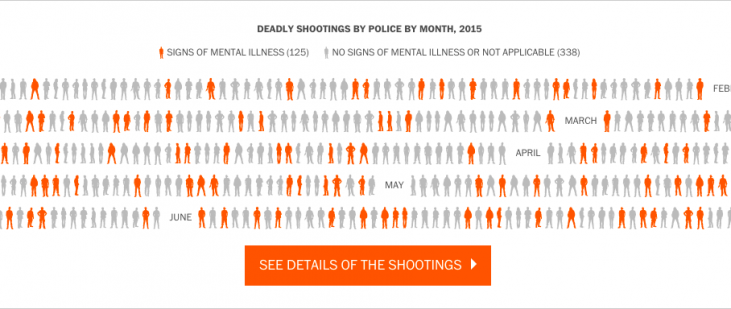

Nationwide, police have shot and killed 124 people this year who, like Page, were in the throes of mental or emotional crisis, according to a Washington Post analysis. The dead account for a quarter of the 462 people shot to death by police in the first six months of 2015.

The vast majority were armed, but in most cases, the police officers who shot them were not responding to reports of a crime. More often, the police officers were called by relatives, neighbors or other bystanders worried that a mentally fragile person was behaving erratically, reports show. More than 50 people were explicitly suicidal.

More than half the killings involved police agencies that have not provided their officers with state-of-the-art training to deal with the mentally ill. And in many cases, officers responded with tactics that quickly made a volatile situation even more dangerous.

The Post analysis provides for the first time a national, real-time tally of the shooting deaths of mentally distraught individuals at the hands of law enforcement. Criminal-justice experts say that police are often ill equipped to respond to such individuals — and that the encounters too often end in needless violence.

“This a national crisis,” said Chuck Wexler, executive director of the Police Executive Research Forum, an independent research organization devoted to improving policing. “We have to get American police to rethink how they handle encounters with the mentally ill. Training has to change.”

As a debate rages over the use of deadly force by police, particularly against minorities, The Post is tracking every fatal shooting by a police officer acting in the line of duty in 2015. Reporters are culling news reports, public records and other open sources on the Internet to log more than a dozen factors about each case, including the age and race of the victim, whether the victim was armed and the circumstances that led to the fatal encounter.

The FBI also logs fatal police shootings, but officials acknowledge that their data is far from complete. In the past four decades, the FBI has never recorded more than 460 fatal shootings in a single year. The Post hit that number in less than six months.

For this article, The Post analyzed 124 killings in which the mental health of the victim appeared to play a role, either because the person expressed suicidal intentions or because police or family members confirmed a history of mental illness. This approach likely understates the scope of the problem, experts said.

In many ways, this subset mirrors the overall population of police shooting victims: They were overwhelmingly men, more than half of them white. Nine in 10 were armed with some kind of weapon, and most died close to home.

But there were also important distinctions. This group was more likely to wield a weapon less lethal than a firearm. Six had toy guns; 3 in 10 carried a blade, such as a knife or a machete — weapons that rarely prove deadly to police officers. According to data maintained by the FBI and other organizations, only three officers have been killed with an edged weapon in the past decade.

Nearly a dozen of the mentally distraught people killed were military veterans, many of them suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder as a result of their service, according to police or family members. Another was a former California Highway Patrol officer who had been forced into retirement after enduring a severe beating during a traffic stop that left him suffering from depression and PTSD.

And in 45 cases, police were called to help someone get medical treatment, or after the person had tried and failed to get treatment on his own.

In January, for instance, Jonathan Guillory, a white 32-year-old father of two who had worked as a military contractor in Afghanistan, was having what his widow called a mental health emergency. He sought help at a Veterans Affairs hospital in Arizona, his wife, Maria Garcia, told local reporters, but the busy hospital turned him away. Jean Schaefer, a spokeswoman for the Veterans Health Administration in Phoenix, said the hospital had no record of Guillory’s visit.

Back home, Guillory dialed 911 twice and hung up. When police responded, he pulled a gun from his waistband and said, “I bet I can outdraw you,” according to Maricopa police spokesman Ricardo Alvarado. They shot him six times.

The dead range in age from 15 to 86. At both ends of that spectrum, the victim was male, suicidal and armed with a gun. On average, police shot and killed someone who was in mental crisis every 36 hours in the first six months of this year. On April 25, three mentally ill men were gunned down within 10 hours.

That afternoon, David Felix, a 24-year-old black man with schizophrenia, was killed by police in the New York apartment building where he lived with other men undergoing treatment for mental health problems, according to police reports. Police said he struck two officers with a heavy police radio after they tried to serve him with a warrant for allegedly punching a friend in the face and stealing her purse.

Two hours later, sheriff’s deputies in Clermont, Fla., fatally shot Daniel Davis, a 58-year-old white man who had recently been released from a mental health facility, according to police reports. Police say he threatened his stepfather and then a deputy with a hunting knife.

And shortly before midnight, police in Victoria, Tex., shot Brandon Lawrence, a 25-year-old white man, a father of two toddlers and an Afghanistan war veteran who suffered from PTSD. Police officers said Lawrence approached them in an “aggressive manner” with a two-foot-long machete. They said they ordered him to drop it more than 30 times.

Lawrence’s wife and another witness have disputed aspects of that account, saying that Lawrence, while armed, was not advancing and was obviously not in his right mind. Convinced someone was coming to kill him, Lawrence repeatedly asked police officers who they were and what they wanted, his wife said.

“He was clearly confused . . . but they didn’t try to talk to him,” said Lawrence’s father, Bryon Lawrence, who works as an Illinois state prison guard.

“Everyone I work with is a convicted felon; I can’t just go up to them and shoot them,” Bryon Lawrence said. “My boy is 25 years old, working 50 hours a week, paying taxes. He was in his own home when they showed up.

“Within six minutes, they murdered him.”

Victoria police declined to comment, citing the ongoing investigation.

Read the rest of the report, originally published by The Washington Post, here.