By Ekaterina Pivovarova, PhD, Judith Edersheim, JD, MD, Justin Baker, MD, PhD, Bruce Price, MD | The Jury Expert | May 2014

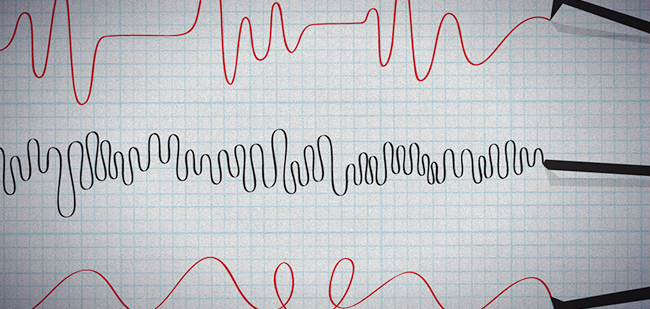

The polygraph, an instrument designed to identify deception, first entered the American courtroom more than 90 years ago. In Frye v. United States (1923), the D.C. Circuit Court excluded expert testimony about the findings from a polygraph. The court noted that the “systolic blood pressure deception test, ” the polygraph, had “not yet gained such standing and scientific recognition among physiological and psychological authorities as would justify the courts in admitting expert testimony.…”

Since then, the polygraph and its modern incarnations have continued to incite legal controversy and debate. The public, press and fact finders are no less fascinated with the polygraph now than they were in the beginning of the twentieth century (Keeler, 1930; Myers, Latter, & Abdolahhi-Arena, 2006). Overwhelmingly, courts have banned results of polygraph testing in criminal proceedings (United States v. Scheffer, 1998). The reasoning for this has largely centered on lack of general acceptance in the scientific community and concerns about prejudicial impact of the findings on the jury (Myers et al., 2006). Nevertheless, the polygraph continues to be widely used by law enforcement, in employment screenings, and for specific types of forensic assessments, such as sexual offender evaluations (Grubin, 2010). Accordingly, litigators, corporate counsel, and trial consultants need to have a current understanding of the scientific underpinnings of the polygraph, the improvements to the instrument throughout the decades, and the ongoing controversies regarding the interpretation of results.