Brandon Monroe for the New York Times

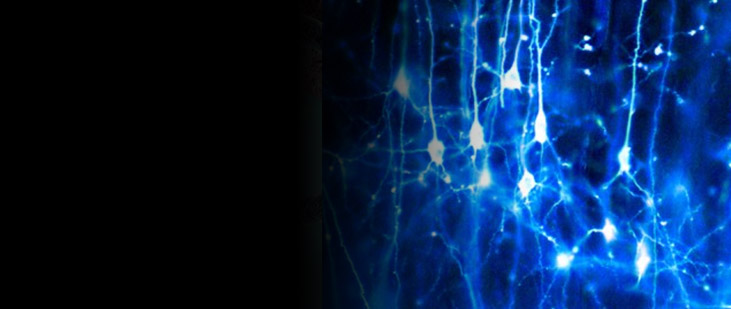

I. Mr. Weinstein’s Cyst When historians of the future try to identify the moment that neuroscience began to transform the American legal system, they may point to a little-noticed case from the early 1990s. The case involved Herbert Weinstein, a 65-year-old ad executive who was charged with strangling his wife, Barbara, to death and then, in an effort to make the murder look like a suicide, throwing her body out the window of their 12th-floor apartment on East 72nd Street in Manhattan. Before the trial began, Weinstein’s lawyer suggested that his client should not be held responsible for his actions because of a mental defect — namely, an abnormal cyst nestled in his arachnoid membrane, which surrounds the brain like a spider web.

The implications of the claim were considerable. American law holds people criminally responsible unless they act under duress (with a gun pointed at the head, for example) or if they suffer from a serious defect in rationality — like not being able to tell right from wrong. But if you suffer from such a serious defect, the law generally doesn’t care why — whether it’s an unhappy childhood or an arachnoid cyst or both. To suggest that criminals could be excused because their brains made them do it seems to imply that anyone whose brain isn’t functioning properly could be absolved of responsibility. But should judges and juries really be in the business of defining the normal or properly working brain? And since all behavior is caused by our brains, wouldn’t this mean all behavior could potentially be excused?

Read the full article in the New York Times. By Jeffrey Rosen, CLBB Faculty member, commentator on US legal affairs, and President and CEO of the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia. Published March 11, 2007.