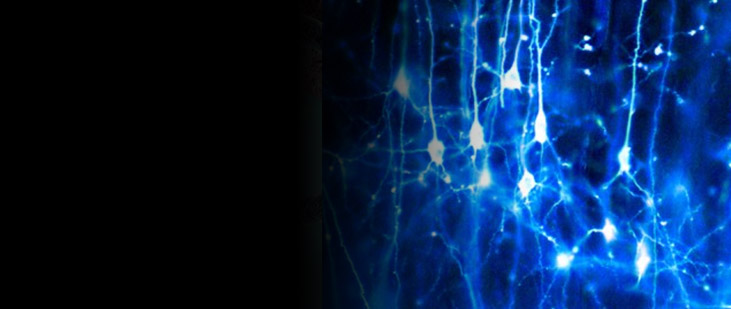

…Rage attacks are violent outbursts grossly disproportionate to the circumstances. Information about sources of frustration or irritation—like the sting of a slap—converge upon a primitive structure nestled deep in the brain stem called the periaqueductal gray. This region is responsible for coordinating essential evolutionary behaviors, from nursing young to self-defense to aggressive attacks. Information from this structure is fed upward to the amygdala and hypothalamus, which refine and coordinate body responses that accompany moments of fury. Among people who are particularly emotionally volatile, surges of violent rage orchestrated by this circuit can be especially dramatic.

Although the behaviors associated with rage attacks—carefully aimed blows, perhaps the use of a weapon—seem as though they must be consciously coordinated and deliberate, this is an illusion. Even complex behaviors that emerge during rage attacks can result from simple electrical stimulation to any of the primitive structures that make up the rage circuit. A jolt of electricity to the right part of the hypothalamus can turn a placid cat into a hissing, clawing demon, attacking nearly any creature within reach. Turn off the current, and the cat returns to its placid state.

Imagine your own cat attacked you during an electrically induced rage attack. Would you blame Fluffy for her behavior? Would you punish her?

These seem like absurd questions until we consider cases of humans whose rage attacks result not from electrodes implanted in the hypothalamus or amygdala, but from tumors or cysts in these regions. In one famous case, a man named Mark Larribus attacked and nearly killed his girlfriend’s young daughter after her crying sent him into a fit of fury. A psychiatrist determined that the frequency and severity of his rage attacks had been increasing over several months and ordered a CAT scan, which showed a tumor compressing his amygdala and hypothalamus. The tumor was removed, and Larribus’ rage attacks, which he described as feeling as uncontrollable as a car skidding across a patch of ice, ceased, and he was cleared of all charges. He was not blamed or punished. If you think this is a fair outcome, you probably believe that it is unfair to punish someone for even heinous violence if that violence results from a clear brain abnormality….

Source: Slate, Oct. 16, 2012. By Abigail Marsh.

[Read the full article at Slate]