Description

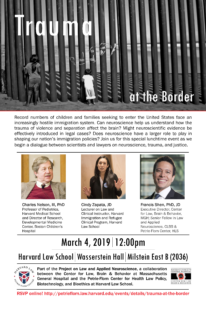

March 4, 2019 at Harvard Law School

At the center of contemporary political debate are the record numbers of migrant families and children at the U.S.-Mexico border. As these parents and children flee the trauma of violence in their native countries, they are now experiencing the trauma of navigating an increasingly hostile immigration system. What can neuroscience tell us about the effects of these traumatic experiences on the brains of the children and adults? And how might the neuroscience of trauma and brain development affect legal cases? Can advances in mobile neuroimaging provide practitioners with real-time brain evidence of trauma? Does neuroscience have a larger role to play in shaping our nation’s immigration policies? This panel session brought together scientists and lawyers to start a dialogue on neuroscience, trauma, and justice.

Videos

VIDEO: Welcome and Introduction, Francis X. Shen

VIDEO: Charles Nelson III, “The Effects of Early Life Adversity on Development”

VIDEO: Cindy Zapata on the impact of refugees’ trauma on their ability to navigate the legal system

VIDEO: Francis Shen, Concluding Remarks

VIDEO: Audience Q & A

Panelists

- Charles Nelson, III, PhD, Professor of Pediatrics, Harvard Medical School and Director of Research, Developmental Medicine Center, Boston Children’s Hospital

- Cindy Zapata, JD, Lecturer on Law and Clinical Instructor, Harvard Immigration and Refugee Clinical Program, Harvard Law School; Leader of 2018 HLS student trip to provide legal services to immigrant families separated in the Karnes Detention Center in Texas

- Moderator: Francis X. Shen, PhD, JD, Executive Director, Harvard Center for Law, Brain & Behavior, Massachusetts General Hospital and Senior Fellow in Law and Applied Neuroscience, Petrie-Flom Center in Health Law Policy, Biotechnology, and Bioethics, Harvard Law School; Associate Professor of Law and McKnight Land-Grant Professor, University of Minnesota Law School

Learn More

Slides

- Charles Nelson III, PhD, “The Effects of Early Life Adversity on Development: Implications for Understanding Trauma at the Border”

Read More

- Francis X. Shen, PhD, JD, “Trauma at the Border: Can Neuroscience Inform Legal Advocacy?”, Bill of Health (February 28, 2019)

- Kathryn L. Humphreys, “Future Directions in the Study and Treatment of Parent–Child Separation,” Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology (December 17, 2018)

- Cindy Zapata, JD, “Heartbreak at the Border: Cindy Zapata on Her Trip to Karnes Detention Center,” The Clinical and Pro Bono Programs of Harvard Law School (November 8, 2018)

- Margaret A. Sheridan and Charles Nelson III, “How to Turn Children into Criminals,” New York Times (May 30, 2018)

Part of the Project on Law and Applied Neuroscience, a collaboration between the Center for Law, Brain & Behavior at Massachusetts General Hospital and the Petrie-Flom Center for Health Law Policy, Biotechnology, and Bioethics at Harvard Law School.