WBUR CommonHealth | By Rachel Gotbaum | July 24, 2014

(part of the Brain Matters: Reporting from the Frontlines of Neuroscience series)

For 32 years, Leslie Ridlon worked in the military. For most of her career she was in army intelligence. Her job was to watch live videotape of fatal attacks to make sure the missions were successful.

“I had to memorize the details, and I have not got it out of my head, it stays there — the things I saw,” she says. “The beheading — I saw someone who got their head cut off — I can still see that.”

Ridlon is now 49 and retired from the military last year, but she finds she cannot work because she suffers from severe post traumatic stress disorder. She has tried conventional therapy for PTSD, in which a patient is exposed repeatedly to a traumatic memory in a safe environment. The goal is to modify the disturbing memory. But she says that type of therapy doesn’t work for her.

“They tried to get me to remember things,” she says. “I had a soldier who died, got blown up by a mortar — he was torn into pieces. So they wanted me to bring that back. I needed to stop that. It was destroying me.”

She has concluded that some memories will never leave her. “Everything I could get rid of as far as memory I think I’ve already done it,” she says. “I think the deep ones that you suffer from, I don’t think anyone can take them away. I don’t believe anyone can. I think the ones I have now, they’re going to just stay there. I’m just going to have to manage them.”

Not long ago, scientists thought of memory as something inflexible, akin to a videotape of an event that could be recalled by hitting rewind and then play. But in recent decades, new technology has helped change the way we understand how memory works — and what we can do with it. Scientists can now manipulate memory in ways they hope will eventually lead to treatments for disorders ranging from depression to post-traumatic stress to Alzheimer’s disease.

“We now understand there are points in time when we can change memory, where we can create windows of opportunity that allows us to alter memories, and even erase specific memories,” says Marijn Kroes, a neuroscientist at New York University.

Kroes is working on doing just that in an NYU lab. On a recent afternoon, he was preparing a 21-year-old female subject for a three-day experiment.

He attached electrodes to the subject’s wrist so he could apply mild electric shocks when certain pictures appeared on the computer. This technique creates a fear memory—which he tests by measuring the subject’s sweat response.

On the second day of the experiment, Kroes shows the subject the same pictures to bring up the fear memory. He then waits 10 minutes — that’s the window, he says, when the memory becomes highly sensitive and vulnerable to change.

“Briefly reactivating the memory weakens or pries the memory loose,” he says. “The connections in the brain for that memory, normally they would re-stabilize again but if you interfere with that process you cause loss of those connections between brain cells, and as a result you lose the memory.”

After he waits 10 minutes, he again shows the images to the subject without the shocks.

“The trick here is, instead of immediately trying to teach people that a situation is safe, you first remind of their emotional experience,” he says. “And now you wait a little while, and this opens up a window of opportunity in which you can update and alter the memory.”

On the third and final day of the experiment, Kroes tests whether he is successful: Did he get rid of the fear memory?

“In her case, if we truly have been able to override the fear memory, she should not show any fear response to those stimuli,” he says. And indeed, “What we now see is a flat line — that means she doesn’t show fear responses. Thus, we see no evidence that she still has a fear memory.”

While scientists long believed that memories were stored in the brain permanently, they now understand that memory is in fact malleable. Kroes says this knowledge — and the ability to specifically alter memory on a cellular level — could lead to new treatments for people with many conditions.

“By understanding that memory is flexible, we can think of ways we can interfere with that flexibility,” he says. “For example, this allows us to potentially come up with new treatments for psychiatric disorders. But you can also think of ways we can understand how to optimize memories in people with degenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s and dementia.”

The hope is that these new approaches can also be used to strengthen memories in patients with memory loss. In the meantime studies are underway in patients with PTSD and other disorders such as addiction. But Kroes warns at this point he and other scientists only have a very early grasp of how these new techniques actually work. And they still have much more work to do before these new discoveries can be translated into effective treatments for the millions of patients suffering from memory and anxiety disorders.

Still, he and other researchers see a major shift in the concept of memory.

“I think it forces us not to think of memory as a video tape where we press play at the moment where we experienced an event,” says Elizabeth Kensinger, an associate professor of psychology at Boston College. “But instead think of the process of recalling a past event as a very active process where our brains are constantly trying to fill in pieces.”

And new technology is allowing scientists to manipulate memory directly in animals.

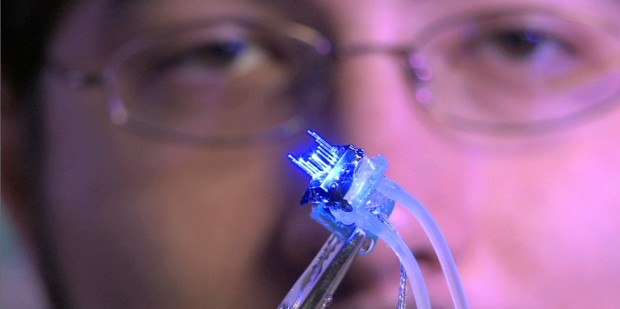

In the lab of Professor Susumu Tonegawa, a Nobel Prize-winning scientist at the MIT Picower Institute for Learning and Memory, researchers are using a powerful new tool called optogenetics to see how memory works in specific cells in real time.

“Moment by moment we our using our memory,” says Tonegawa. “It’s important for us to know how we form a memory, how we record a memory and how it goes bad under certain conditions.”

With optogenetics, scientists use lasers to identify specific memory cells and also to manipulate those cells.

Recently, Tonegawa’s lab used optogenetics to implant false memories into lab mice. Now, his lab is working on altering memories of mice with depression and symptoms of post-traumatic stress. The idea is to modify painful and stressful memories.

People like Leslie Ridlon, the veteran with PTSD, are waiting for the progress in labs to reach the point that it can help them.

“If someone took away all the bad memories and I could function every day, that would be great,” she says.

Read the full story on WBUR, or check out more from the series Brain Matters: Reporting from the Frontlines of Neuroscience.